Elizabeth McSheffrey — National Observer

A whopping increase in the number of animals used for by Canadian scientists for research and education purposes is sparking outrage from animal advocates across the country.

The Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC) recently released its annual report for 2014, revealing a 24 per cent spike in animal use from the previous year. Roughly 3.75 million animals — primarily fish, mice, and birds — were used for education, medicinal, regulatory testing, or research purposes by over 200 certified institutions in Canada, up from just over three million in 2013.

Animal rights groups argue that these numbers show that Canada isn’t respecting its commitment to ‘the 3Rs’ guideline 0f humane animal research: replacement of animals wherever possible, reduction in the number of animals used per experiment, and refinement methods to minimize suffering and improve subject welfare.

“With the advent of a lot of new non-animal methods, we should at least be seeing a decrease,” said Dr. Elisabeth Ormandy, executive director of the Animals in Science Policy Institute (AISPI), a non-profit based in B.C. dedicated to building a more ethical culture of science. “This 24 per cent increase really raises questions about how seriously the principle of replacement is taken in Canada.”

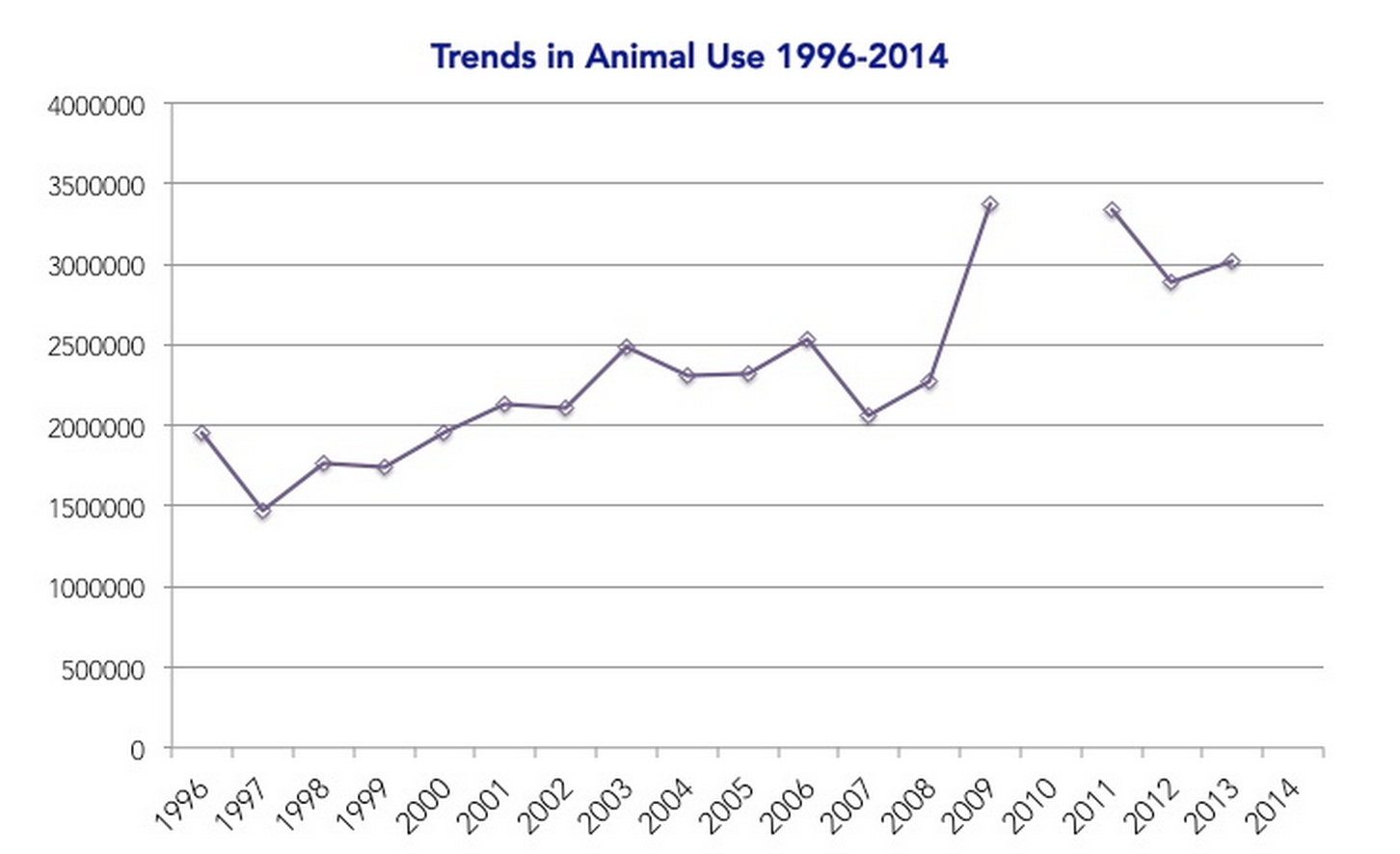

An upward trend of more than a decade

While the ‘three Rs’ are not a legally-binding principle in Canada, they are “at the heart of all CCAC policies and guidelines.” The Canadian Council on Animal Care is a federally-funded, national organization that sets, maintains, and oversees the implementation of ethical standards for use of animals in Canadian science.

And despite advancements in animal replacement technology, like virtual reality dissecting, computer modelling, cell manipulation, 3D-printing, and in vitro work, animal use in Canadian science has generally increased since the mid-1990s, as has the level of overall pain and distress the animals could be exposed to during the studies.

In 2014 in particular, AISPI pointed out that 29 animals were subjected to “procedures which cause severe pain near, at, or above the pain tolerance threshold of unanesthetized conscious animals” for the purposes of education, despite a 1989 CCAC policy that deems such painful experiments unjustified if conducted solely for classroom instruction or demonstration of established scientific knowledge.

“We all really want to find amazing cures or treatments for socially prevalent diseases, however, there might be some people who say that regardless of being able to develop treatments for those diseases, there are certain means of getting there that are unacceptable,” said Ormandy.

“We would like to be able to see more meaningful public conversation about what’s acceptable to the citizens of Canada.”

CCAC doesn’t have details on its own statistics

CCAC chairman, Dr. René St-Arnaud, said there could be several reasons for animal use increase in 2014, including increased research funding, an increased number of institutions participating in their data collection, or an increase in wildlife observation studies where large populations of animals are counted in the field, but left untouched in their natural habitats.

He wasn’t however, able to confirm anything of those theories, nor could he offer any extra information about what kinds of painful experiments the 29 animals were subjected to for education or whether any scientific gain was made as a result of the experiment.

“I don’t know what they are and I don’t know what they concern,” he told National Observer. “It would be my comprehension that the animals were probably anesthetized throughout the procedure and did not suffer any pain or stress.”

The details of experiments, their results, and their methods are recorded with the individual animal ethics committees that work for the institutions certified by the CCAC, he explained, but do not go into its annual report. When asked if the CCAC — which is responsible for the implementation of Canada’s animal welfare standards — had access to those details anywhere in its office, St-Arnaud said he wasn’t sure.

The animal ethics committees only report to the CCAC every three years, when the CCAC conducts inspections of the institutions. When asked how the public could trust the CCAC to properly oversee animal care in science given that it only visits its member institutions once every three years, the chairman responded:

“We can’t be on site every day. The on site every day presence is the animal care committee whose membership and functioning is part of the CCAC guidelines.”

St-Arnaud assured National Observer that the CCAC’s system has worked well since its implementation in 1968, and that interpreting Canadian animal welfare in science by the numbers alone could be misleading. He accused AISPI of “raising points based on the numbers only without any context,” but when asked if the CCAC should provide that context in its annual report to ensure the numbers aren’t misinterpreted, he said:

“I don’t know how to answer that. There are community representatives on every animal care committee and they are the people who ask questions that are not related to science, who ensure the animals do not experience any stress or pain, that there is enrichment to their milieu, and that the numbers are reduced and that’s part of how the Canadian values and the viewpoints of the public are represented at the local level. Using statistics to express that is challenging and we would like to have a better way than strict numbers, but at the moment that’s what we have.”

More transparency in the system

Ormandy of AISPI said an organization funded by taxpayers should be more accountable than that and had a hard time believing the CCAC had no extra information on hand to supplement the numbers. She described the 24 per cent increase in animal use, the lack of answers, and the off-loading of responsibility to animal ethics committees as “red flags” that the system requires more transparency.

“I think that the animal numbers that get reported are just the start of a bigger conversation and I think there are some important questions,” she said. “Why aren’t government agencies putting research dollars into [animal replacement] techniques and experiments? How do we get non-animal alternatives on the map so they are the first point of call rather than this default position that we’re going to use animals because that’s what we’ve always done?”

One organization that does offer funding for animal replacement research in Canada is Lush, a U.K.-born cosmetics retailer famous for its stance against animal testing, and its emphasis on organic, ethically-purchased materials and handmade products. Its annual ‘Lush Prize’ of £250,000 (roughly $430,500) rewards groups and individuals whose research makes meaningful leaps towards ending animal testing, and in 2016, will specially emphasize young researchers in North and South America.

It too, condemned Canada’s increase in animal use for 2014, and the lack of accountability for it from the CCAC:

“I’m sure there are many people who are now asking them these questions, and the fact that they’re able to skirt around that and not provide those answers also just kind of shows a lack of transparency and accountability for the role that they play in the well-being of animals,” said Lush Canada’s charitable giving manager, Tricia Stevens.

“When you look at what the non-animal alternatives that exist are, it is alarming to see an increase in the double digits, which at the end of the day, results in the loss of lives of animals.”

This article originates at www.nationalobserver.com

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto