Bruce Bell —

Bruce Bell —

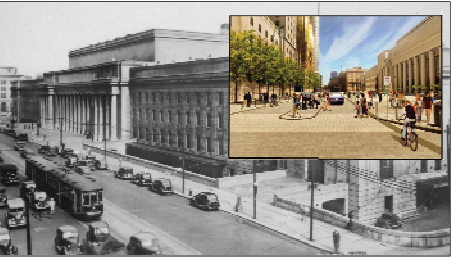

For the past few years Union Station on Front Street has been shrouded in white plastic sheets like a massive present waiting to be opened.

When that day comes (maybe next year?) the colossal train station will be unveiled looking like it did when first opened in 1927. With all the new gigantic glass-and-steel skyscraper construction projects going on around it, the refurbished Union Station will have one thing the others don’t: history.

In 1858 the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) built an over-sized wooden shed on Front Street just west of York Street and named it Union Station. Our first.

In 1870 the Grand Trunk Railway began to build a more modern train station to replace their wooden structure that was getting overcrowded.

It was decided what Toronto needed was a modern, massive and magnificent train station to match the equally grand buildings that were springing up in the Downtown core.

The new Union Station (our second) was to be a gigantic building project and because the bulk of this new station was built on the soft ground of the harbour, a gigantic platform was created so the entire building would float on the mud of the then harbourfront.

This new state-of-the-art train station complete with three towers rising above its great shed opened on July 1, 1873.

It was built in a time when North American cities were still very much influenced by European architecture and this, our second Union Station, was built in the very French Second-Empire style then all the rage in Paris.

This enormous train station that stood between York Street and the CN Tower was demolished in October 1927.

A few weeks earlier in August the Prince of Wales (later the uncrowned Edward VIII) opened a new Union Station—Toronto’s third and the one we have today—on Front across from the Royal York Hotel.

Although the new Union Station was basically complete in 1920, it sat unused partly because of political wrangling and for the small fact that the train tracks had yet to be moved in place.

The massive new station built by visionary Toronto architect John Lyle (Royal Alexandra Theatre 1906) in the grandiose Classical Revival style with its magnificent colonnade of mighty Doric columns took almost two decades from its groundbreaking in 1915 to get into full operation.

Construction was halted due to WWI then in the 1920’s due to political haggling but eventually the tracks were in place and this superlative building took its place in the pantheon of Toronto’s eye catching landmarks. When the outdated yet magnificently opulent old French-inspired Union Station was finally demolished passengers would have to enter the Great Hall of the new Union Station, go back outside and walk all the way to the former station’s platforms across York Street.

Construction was halted due to WWI then in the 1920’s due to political haggling but eventually the tracks were in place and this superlative building took its place in the pantheon of Toronto’s eye catching landmarks. When the outdated yet magnificently opulent old French-inspired Union Station was finally demolished passengers would have to enter the Great Hall of the new Union Station, go back outside and walk all the way to the former station’s platforms across York Street.

This frustrating inconvenience continued until 1930 when finally the viaducts over Bay and York Streets were built and the new platforms and tracks were moved into place.

Even so after years of skepticism everybody agreed that the new Union Station was breathtaking.

From the moment you cross the threshold into the great hall you are greeting with the site of two gigantic Corinthian columns flanking the entrance to the trains. Rumoured to be a symbol of Freemasonry, these are replicas of the columns that once stood at the entrance to the ancient Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. (Masons date their origins back to the building of the Temple.)

A powerful-yet-subtle reminder to a time when Masonic symbolism was embedded into most public buildings here in Toronto. The interior is set off with a massive vaulted ceiling that arcs itself down to rows of clerestory casement-style windows, bathing the great hall in natural sunlight. Surrounding the frieze are the names of Canada’s largest cities along the route of the transcontinental railroad.

There are a few spelling mistakes etched in the Missouri Zumbro sandstone frieze: the first is the misspelling of Sault St. Marie-—it should be Ste.—and the spellings of Québec City and Montréal are in English without the accents above.

Great train stations are very much products of their times with the melding of the industrial age together with the arrival of the steam engine.

In metropolises all over the world magnificent structures were built to house their train stations including New York City’s Pennsylvania Station, an eye popping colossuses.

It took 15 years to construct Penn Station but when it finally opened in 1910, with its magnificent iron arches, gigantic stone façade and intricate glass ceiling, the new train station was instantly hailed as a masterpiece of the modern age. However, at barely 50 years old the destruction of Penn Station in 1963 to make room for a new Madison Square Garden caused a public outcry that would provoke an architectural preservation movement both in the States and here.

In the 1970s Toronto’s Union Station with its thick row of sweeping exterior columns was also threatened with demolition. In fact we’ve almost lost it twice but through community efforts and with the help of City Hall the vast historic building was saved. When the renovated Union Station opens next year it will have a larger pedestrian concourse under Front Street and as if to acknowledge our great railway heritage, the platform and station for the new train link to Pearson Airport is being built where Toronto’s second Union Station once stood just west of York Street.

Union Station continues to serve millions of travellers from all over world (and locally) who get their first glimpse of Toronto through the monumental entrance of this great train station that soon is going to look a whole lot better once the wrapping comes off.

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto