By every measure, Ontario is much deeper in debt than California, the poster child for fiscal irresponsibility, finds a new study released today by the Fraser Institute, an independent, non-partisan Canadian public policy think-tank.

“California is routinely criticized by pundits, politicians and economists for its inability to control spending and reduce deficits. Yet Ontario, with a fraction of California’s population and a significantly smaller economy, carries a debt load almost twice as large as California’s,” said Sean Speer, associate director of fiscal studies at the Fraser Institute and co-author of Comparing the Debt Burdens of Ontario and California.

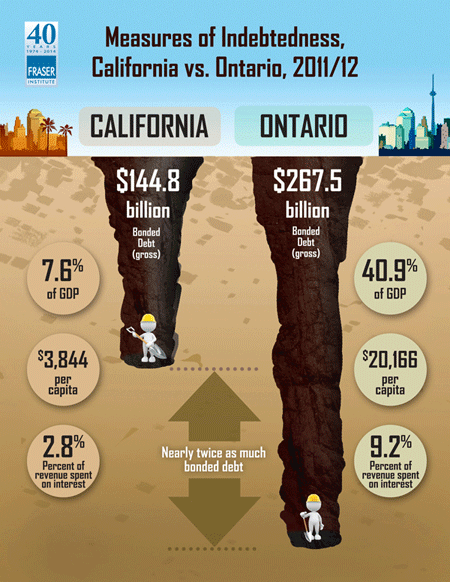

The numbers tell the tale. Despite the province’s smaller size, Ontario’s $267.5 billion (Cdn) outstanding government debt is higher than California’s $144.8 billion (US). As a share of the economy, Ontario’s bonded debt (the part of a government’s debt represented by bonds) is 40.9 per cent compared to California’s 7.6 per cent.

Every Ontarian owes $20,166 (Cdn) compared to $3,844 (US) for every California resident

“Ontario’s debt relative to the size of its economy is more than five times larger than the same measure for California,” Speer said.

And when boiled down to a per person basis, every Ontarian owes $20,166 (Cdn) compared to $3,844 (US) for every California resident.

So why should Ontarians care?

The effects of government debt are wide-ranging. For example, when government borrows, it competes with the private sector, limiting the ability of businesses to borrow and invest in plants, machinery, equipment, and research, as well as training and development of staff.

Moreover, the higher the government debt, the greater the burden on taxpayers who are saddled with government debt servicing costs (a.k.a. interest payments).

Ontario, for example, devotes 9.2 per cent of its revenues to interest payments, a figure more than three times higher than California’s 2.8 per cent. Interest payments eat up money that could be used for vital services such as health care, education, infrastructure investment and tax reductions.

Furthermore, according to the most recent information available, interest costs will represent the fastest growing part of the provincial budget from 2012/13 to 2015/16, increasing at 5.5 per cent annually—more than twice the projected rate of growth in health care expenditures.

So what can be done?

“The good news is that Ontario’s path to fiscal responsibility doesn’t have to involve draconian cuts. By merely limiting the growth of government spending, Ontario can back away from the edge of the fiscal cliff,” Speer said.

The study points to a recent analysis co-authored by University of Calgary professor Ronald Kneebone. Ontario’s finances may greatly improve, says Kneebone, if Ontario capped program spending growth at four per cent per year. Such growth rates represent a stark departure from pre-recession trends, which included spending growth on education at a whopping 10 per cent annually.

Back in California, the state government stabilized its fiscal situation by combining spending cuts with tax increases, which, while temporarily stabilizing, discouraged business development and investment, and made the state even less tax competitive.

“Ontario is in a bad situation—worse than California. As numerous reports have shown, including this most recent analysis, if the provincial government wants to steer Ontario towards financial sustainability, it should rein in spending,” Speer said.

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto