Daniel Libeskind is the architect Toronto loves to hate the most.

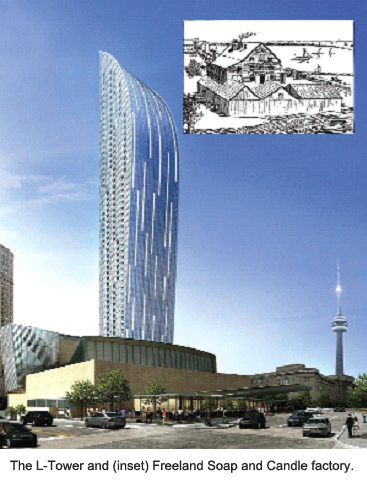

He has the distinction of constructing one of the most controversial and unsightly structures in our city—the new addition to the ROM—while at the same time building one of the most striking; his soon-to-be-completed L-Tower.

For the past few years I have watched his L-Tower rise at the corner of Yonge and The Esplanade and I have been awed at its ascendancy.

I can only assume that some my neighbours don’t share my opinion as the sleek 58-story condo can be a view blocker for sure.

American architect Daniel Libeskind, born in Poland in 1946 to Holocaust survivor parents, is best known for his Jewish Museum in Berlin. And also as the winner of the invitational competition for New York City’s World Trade Center redevelopment in 2002.

While his Berlin project is magnificently poignant, other architects were eventually chosen to construct the new WTC site.

However the one component of Libeskind’s original plan was spared: the new tower’s symbolic height of 1,776 feet.

Another reason I like his L-Tower is that its stylish presence does justice to an incredibly important and historic part of our city.

Originally the area around Yonge and Front was once the site of the Freeland Soap and Candle factory; one of Toronto’s first industries.

In his day the name Peter Freeland was known to all for it was his candles that lit the homes of Toronto’s first citizens in the days before gas, electricity and light bulbs.

Peter arrived in New York from Glasgow Scotland in 1818 then after a time he and his brother William traveled up to Montreal where they set up a soap and candle factory. In 1830 they moved here (then still called York) where they bought land including the ground covered by water at the foot of Yonge Street when Front Street was still our harbourfront.

The population of the town was about 5,000 and with no rail-links or telegraph yet in place, building his factory with its enormous wharf was a Herculean effort.

The main building was 90ft long by 40ft wide, three storeys high and had huge double doors at each end.

Because most of property was covered with water, the factory had to be built on cribs sunk with stones. He imported his iron soap-kettles from Scotland, the candle molds from the US and the rest of the machinery was brought in from eastern Canada.

All of this equipment arriving by sailing ship and in a time when all business transactions were written by hand using quill pens (the average quill lasted only a week) and ink made from charcoal or soot combined with a sticky substance made from gum, glue or varnish.

Hard to believe in our modern world today but a large factory did get built, just as our great city was emerging out of the forest, without the use of a cellphone,

Internet, email, paved highways, air travel, electric power or printer ink.

During the winter, blocks of ice used in warm weather for hardening the candles in the moulds. They were cut from the frozen harbour and stored in the basement of the American Hotel.

At one time stood across the street where the massive EDS building now stands).

Wild ducks were so plentiful around his wharf that Mr. Freeland used to shoot them from his factory windows.

One day his neighbour Richard Tinning was walking along the shore when some ducks flew up from the water, startling him. So he fired his gun without looking where the shot was going and his bullet crashed into the window of the Freeland factory.

Mr. Freeland ran out, armed, to resist what he thought was a raid.

No one would blame him. since Peter Freeland was an ardent reformer.

During the Rebellion of 1837 the factory played an important part where under the guise of darkness he would make bullets using candles molds.

In 1841 the first gas lamps were being lit in Toronto and Freeland’s candles started to decline in popularity.

By the beginning of the 1850s the railroad moved in and with it the once quaint waterfront with its Esplanade was replaced with the belching smoke of the steam engines.

The Freeland’s Candle and Soap factory went the way of the dinosaur after the death of Peter Freeland in 1861 and today is remembered with Freeland Street just east of Yonge running between Lakeshore and Queens Quay.

As the decades came and went the area around Yonge, Front, Scott and The Esplanade became home to the vast Yonge Street Wharf, then the entrance to our city much like Pearson Airport is today.

In 1866 the block became the site of one of our first train stations, the Great Western. However by 1927 with a massive landfill underway, The Esplanade ceased to be our waterfront and the future L-Tower site—once a bustling port-of-entry—became land-locked.

In 1952 the former Great Western station, by then a fruit and vegetable market, burnt down and the O’Keefe Centre for the Performing Arts (now the Sony Centre) was constructed on its site and opened in 1960.

The gleaming L-Tower, built adjacent to the Sony Centre (thus creating a gargantuan candle-like letter ‘L’) is an ideal icon for this historic corner.

As we all know…it could have been so much worse.

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto