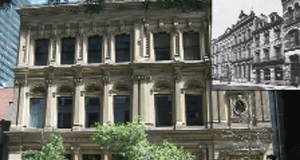

The Consumers Gas Building at 19 Toronto St, (now home to the exclusive Rosewater Supper Club) is a perfect example of how Toronto wanted to present itself in the late 19th century; elegant, sophisticated and powerful.

Built by the team of Robert Grant and David Dick, this was to be like no other office building of its day, with rich French-inspired detailing, fluted pilasters, arched windows topped with carved shell forms and a main entrance flanked by polished red granite Ionic columns.

Today the building’s beauty is matchless but it in its day it was just one of hundreds like it all gorgeously detailed an architectural reality that would be their downfall decades later.

It was first built in 1876 with additions added 1882 and 1899 to be the head office of the giant Consumers Gas conglomerate in the days before electricity when coal was king. Consumer’s Gas had by 1884 supplied Toronto with 110 miles of main lines, 240 million cubic feet of gas made from coal per year and it was this by-product of coal that saw Toronto go from being a quiet colonial outpost with a few wood-burning stoves to becoming am economic powerhouse.

Burning coal at the gigantic, belching Consumers Gas complex blackened the rich terra-cotta, marble and brick façades of almost every building in Toronto. Some of the complex still survives in part in the Berkeley and Front area.

When the time came to destroy these historic buildings people forgot how beautiful they were beneath that soot and grime. So down they came, with little or no protest.

It was also coal gas that killed thousands every year as it entered people’s lungs and put the city under a thick dirty fog for the next 100 years.

What we would call pollution today, back then was called prosperity.

While only one block long today, Toronto Street 200 years ago was a major thoroughfare.

In 1793 Gov. John Graves Simcoe laid out the Town of York with a western boundary at George Street. A few years later Peter Russell replaced Simcoe and expanded the town’s frontier to present-day Peter Street (named for himself) and on June 10, 1797 Toronto Street came into being.

Back then the newly constructed Yonge Street didn’t extend its length to Lake Ontario as it does today but instead it started its journey northward at present-day Queen, then called Lot Street. Properties on the west side of Toronto Street stretched well past present-day Yonge Street, thus preventing its further construction below Queen.

Farmers coming into York via Yonge Street would have veered off Yonge and continued their journey to the market down Toronto Street south to present-day Wellington (then called Market Street).

In 1818 the plan was revamped with Yonge Street now stretching its way down to the lake (then Front Street) and Toronto Street was closed south at King and Adelaide at its northern end, creating the block-long street we have today.

In the mid 19th century with Toronto growing rapidly, new public buildings were needed including a more modern post office. Overcrowding overcame the 6th Post Office (1845-1852) on Wellington just west of Leader Lane, located in a small room in a damp dark basement with a low ceiling.

The site chosen for the new post office would be on Toronto Street just across the street from where supporters of Mackenzie’s ill-fated 1837 Rebellion, including Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews, met their deaths on the gallows that at one time stood there. The 7th Post Office (still standing at No 10) built by architect Frederick Cumberland in 1853 was seen as a departure from the unadorned Georgian Style and was to lead the way in building monumental Roman- and Greek-inspired style structures in Toronto for next 50 years.

In 1872 a larger post office was needed. Architect Henry Langley was hired to build one of the most beautiful buildings in our city, the opulent General Post Office, our 8th, on Adelaide at the head of Toronto Street.

This magnificent structure created a grand vista and made Toronto Street a sought-after address for the up-and-coming industrial barons of the day.

In the 1950s Toronto began to reorganize its postal system and the grand General Post Office was re-named Postal Station Number 1 that was, in 1958, destroyed with little or no protest. In 1960 the William Lyon Mackenzie Federal Building at 30 Adelaide St. E. replaced Langley’s lavish post office and after a major face-lift in 2001 it reopened as the State Street Financial Centre.

In 1959 another gem was destroyed on Toronto Street: the Temple Chambers a 3-storey Renaissance-styled office building built in 1873 just north of the Consumers Gas Building.

It was replaced with a small 1-storey building which opened as the Blue Flame Room; part of the Consumers Gas conglomerate.

In the 1960s, after the burning of coal was replaced with the more clean-burning natural gas, the Blue Flame Room had a window display featuring mannequins wearing aprons and pearls standing over gas-ranges as if stirring a pot.

The showroom offered cooking classes and was designed to show the modern homemaker how clean natural gas was. It closed in the mid 1970s and today sports a modern mirrored façade. It is home to an ESL school.

Toronto Street, while still a classy address in its day—thanks to the grand buildings that once lined its sides—was the epitome of business success.

Thankfully not all the stunning 19th-century architecture is lost on Toronto Street, for all you have to do is give yourself a few moments admiring the stunning façade of the Consumers Gas Building to get an idea of how most of Downtown Toronto once looked.

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto