By Stig Harvor –

Toronto’s street system was never designed to handle the traffic volume now imposed on it. The effect of cars Downtown is clear. They clog up our streets. They slow down public transit. They threaten the safety of pedestrians and force them on to narrow sidewalks. They pollute the air. They block views. They demand large parking areas, expensive to build underground, unsightly when at ground.

Toronto’s street system was never designed to handle the traffic volume now imposed on it. The effect of cars Downtown is clear. They clog up our streets. They slow down public transit. They threaten the safety of pedestrians and force them on to narrow sidewalks. They pollute the air. They block views. They demand large parking areas, expensive to build underground, unsightly when at ground.

Ideally people living Downtown should have less need or want of cars. City surveys in 2001 indeed found that in the expanding western King-Spadina area and the eastern King-Parliament area, 38% of residents did not own cars. Bicycles were owned by 60%. This is encouraging. Almost two-thirds got to work either by public transit (29%), bicycle (1%) or walking (32%).

Based on such statistics, some citizens in the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood are now trying to reduce the existing bylaw ratio of 0.8 parking spaces for every residential unit to 0.65. Many buyers, however, still want parking and developers provide it because attractive alternatives to private cars are little known, inconvenient or hard to use.

One obvious alternative in a big city is good public transit. But our Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) service has actually deteriorated as a consequence of destructive downloading policies forced upon cities and towns by our former provincial government. Its ill-advised tax cuts also depleted public funds.

The provincial government, however, is not wholly to blame. The federal government, with Paul Martin as Finance Minister, in 1995 started the ill-fated sequence of downloading government services by cutting back contributions to the provinces. Ever since, the federal government has been awash in cash while provinces and municipalities have been struggling. It is a highly irresponsible way to run a country.

Provincial support in the 1950s and onward was essential to the construction of Toronto’s present and indispensable subway system. Meanwhile, the Greater Toronto Area has grown by leaps and bounds. Yet no significant, major, new subway has been built for 26 years.

The only exceptions have been the eastern RT extension from Kennedy to McCowan in 1985, and the politically motivated but so far under-utilized eastern extension opened in 2002 from North York to Don Mills which fell short of closing the logical loop to Scarborough Town Centre.

Today significant provincial and federal support for public transit is sadly lacking. Private wealth is increasing at the expense of public services. Welcome to the brave new world of neo-conservative economics!

A useful and effective alternative to private car ownership is a car rental system known in Toronto as AutoShare. Members rent cars at reasonable rates for variable lengths of time, usually just a few hours. For someone not using a car daily, it is an economical way to use a car when needed.

So far, five enterprising condo developers have implemented the idea. They provide those cars in their buildings for the use of their residents. May that idea spread and flourish!

The ownership of a car is a privilege whose public costs must be paid for just like the ownership of a house.

Studies by the Canadian Automobile Association and the trucking industry claim that drivers cover the direct public costs of our vast transportation network, such as the building and maintenance of streets and highways.

Indirect costs are ignored. They are real but difficult to calculate. They include health expenses caused by pollution and accidents, and public costs of traffic control, policing and courts. There is environmental damage. There are the vast costs associated with urban sprawl made possible by cars.

Despite registration and license fees and high gasoline taxes, it is therefore debatable if car and commercial vehicle owners pay the full public costs of providing the services required and caused by them. Any attempt, however, to recover for public purposes such as transit, some of the total public costs of cars, is immediately met with an outcry by car owners.

When Mayor David Miller during the municipal election campaign a year ago made an off-hand remark about the possibility of tolls on the Don Valley Parkway, there was an instant, negative public reaction. Some of his supporters feared he had lost the election at that moment. That he won gives some hope to the possibility of a future rational debate on toll roads.

Miller recently visited London, England. He was impressed by the success of the central city road tolls of $12 daily for peak hours called congestion charges. They were introduced just two years ago by its energetic mayor, Ken Livingston. If Miller had also visited Oslo, the capital of Norway farther north, he would have found a city toll-road system already in full bloom for 14 years.

Interestingly, the Oslo toll idea met strong opposition when first proposed in the 1980s. A year before its introduction in 1990, 65% of the population opposed tolls. Seven years later almost 60% still opposed them. It took political leadership and courage to implement the program which is to be reviewed in 2007.

The Oslo region has a population of 500,000. Half that number of vehicles entered the city daily in 1997 and paid around $120 million annually in $2.50 tolls for cars and $5 for trucks. As a political sop to drivers, only 20% of the revenue is allocated to improving public transit. After administration costs of 10%, the remaining 70% goes to improving the road system.

The volume of traffic in centretown Oslo was not noticeably reduced after the first seven years of tolls. It is estimated tolls would have to be raised three to five times to have a significant impact on traffic volume. But the movement of traffic had improved considerably by the building of tunnels and other road construction. Transport and taxi companies showed considerable savings leading to the elimination of 100 taxis.

There were also improvements in the appearance of important public spaces at the waterfront. Oslo had its on-the-ground version of the Gardiner Expressway before a new tunnel was built partly with toll money along the central waterfront facing the imposing city hall.

Another tunnel below the former industrial harbour area is just starting. This tunnel will free up land for residential and commercial development close to centretown and the railway station. A new opera house is already under construction there on the water’s edge.

In Europe waterfronts are being revitalized. In Toronto we only talk about it.

Why are private cars so popular? Obviously they offer the convenience and flexibility of getting to places at all times and carrying goods when needed. A lesser, more subtle attraction is their ability, like our clothing, to publicly exhibit status, taste, and—at times—wealth.

The low density and sprawl of so much city growth in the suburbs contributes to the virtual necessity of private cars in order to live there. Yet they multiply to the point where they create congestion interfering with their own valued mobility.

They also foul up the air we breathe. But when it comes to cars, we human beings are not a thoughtful species despite our brainpower. How explain the recent rash of over-sized so-called sports utility vehicles (SUVs)? They have nothing to do with sports except to compete for size and muscle. They are unsuitable for crowded city streets because of their bulk.

To add insult to injury, governments caved in to car manufacturers and the oil lobby and lowered the pollution emission controls on these gas-guzzling hogs by classifying them as light trucks rather than cars.

The popularity of SUVs can probably be traced to a combination of income tax cuts and a sense of general insecurity in our volatile world. Tax cuts transferred public money into private pockets to spend more on cars. A sense of insecurity fostered the need for a feeling of increased individual protection.

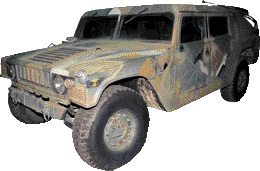

The ultimate expression of these base instincts is the outrageous adaptation to civilian use of the contemporary American war vehicle, the Hummer. The now common Jeep was also developed for wartime use, but never had the openly aggressive look and association with brute force of the Hummer.

Pre-Second World War Germany under Hitler encouraged the sale of exquisitely made war toys. The introduction of the civilian Hummer for adults and the avalanche of violent and very graphic video games for children may be precursors of more militaristic societies.

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto