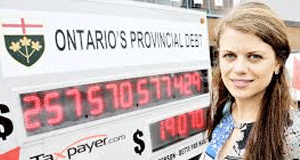

Candice Malcolm —

Nobody likes paying eco-fees in Ontario. Many view it as a tax; an extra fee tacked onto purchases, sending cash flowing into the vast government void — all in the name of being environmentally responsible.

Canadian Taxpayers Federation

Ontarians are environmentally conscious and happy to pay their fair share when it comes to recycling. Taxpayers, however, are rightly cautious about fees that are set, imposed, and collected by government.

Candice Malcolm

Canadian Taxpayers Federation

In this sense, Ontario’s Waste Reduction Act, or Bill 91, seems like a smart move by Premier Kathleen Wynne’s government.

The eco-fees are gone, and consumer goods will continue to be recycled.

However, when you look deeper into Bill 91, it’s clear consumers are going to foot an even larger eco-fee, this time hidden, while their government does nothing more to improve the environment.

Right now municipal facilities handle the processing and recycling of consumer goods packaging.

The cereal box you toss in your blue bin gets picked up by your city recycling service, taken to a municipal facility and from there it is recycled.

The recycling bill is covered through eco-fees and by municipal taxpayers, paying through their utility bills or property taxes.

The Wynne government’s Bill 91 would shift the cost to industry.

This means it will be up to the manufacturer to pay the bill for recycling their products’ packaging.

This idea of making the producers responsible for recycling their own products is a good one in theory, but not the way Bill 91 makes it happen.

Instead of transferring responsibility for recycling onto industry, this act only shifts the costs.

The recycling facilities would continue to be run by municipalities. This is so that unionized municipal employees don’t lose their jobs or control in the waste diversion cycle, which is an obvious driver of costs.

If you actually made industry responsible for recycling their products — as is done in most Canadian provinces — instead of just sending them the bill, industry would be driven to find a more efficient process and thereby lower the costs for both themselves and their customers. They would also have an incentive to save money by reducing their packaging.

The government could still set the standards, but companies would have more independence in the recycling and waste diversion process.

Lower recycling costs and less waste is a double win for taxpayers concerned with the environment.

But by leaving control with the municipalities and sending the bill to industry, union contracts will just continue to grow — as local politicians will have no incentive to drive a good bargain with their recycling workers — and the increased costs will inevitably be passed along to consumers through higher prices for everyday items in Ontario.

Premier Wynne thinks she’s being clever by forcing these costs onto industry and leaving her union pals in charge.

Meanwhile she also pats herself on the back for eliminating the much-hated eco-fees.

But her government isn’t helping the case for industry to create more jobs in Ontario when it tacks extra costs and fees onto the bottom line of businesses in the province.

In a nutshell, Bill 91 exemplifies everything wrong with the Wynne government’s economic management.

Double standards, union favouritism, red tape, and an expectation that jobs are created out of thin air.

If this bill passes, you might not see an eco-fee on your bill anymore, but you’ll certainly be paying it every time you go shopping in Ontario.

This article first appeared in the Toronto Sun on Thursday, November 21

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto