Brendan McAleer —

Ever try to heel and toe in a pair of wooden shoes? Me either, but I’ll bet it’s no picnic. And yet, more and more manufacturers would have you shift gears in a manner first popularized by the Dutch motor industry: the Continuously Variable Transmission.

Hoo boy, that phrase cleared the gearheads out in a hurry. One of Harry Potter’s wand-flinging semi-Latinate exhortations doesn’t have the magical auto-enthusiast-repulsion of a good Continuous Variableus! Mostly, people who like to drive don’t like to drive ‘em.

But wait, here’s Subaru offering a CVT in their entirely new WRX, a car that many are praising as one of the best rally-rocket Subie to come along in years. Has the world gone mad?

Not at all. In fact, the CVT’s spreading popularity as the automatic transmission of choice is actually probably a good thing. Your fuel economy goes up. You can keep the engine singing in its powerband. A CVT might not have any gears, but that doesn’t mean it’s bad for gearheads.

To find the first mention of a variable ratio transmission, we have to look way back, and possibly learn to read mirror-written Italian. While you won’t find a sketch of a scrappy four-banger in Leonardo da Vinci’s notebook, you will find the plans for a stepless transmission with a theoretically infinite range of ratios. It’s hardly new technology – Leo jotted down the idea in 1490.

CVTs made their first automotive appearance in Dutch-made DAFs.

Early uses included power-operated milling and sawing, and the device was used in cars and motorcycles as early as the late 1800s. While the CVT was first popularized in low-powered scooters and the like, its first widely accepted automotive appearance was in the Dutch-built DAF 600. DAF called their version the Variomatic, and it would give the tiny, 590cc-engined family car some very odd characteristics.

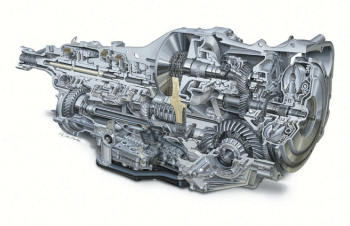

First though, a look at what a Continuously Variable gearbox actually is, because they aren’t all the same. For instance, the Prius can claim to have an infinite number of gears between its highest and lowest ratios, but that’s a result of its planetary drive taking in a number of power outputs (from both electric and gasoline sources), and shunting the power around as needed.

More commonly, when we’re talking about a CVT-equipped passenger car with a conventional engine, the transmission in question is a belt-drive. Imagine, if you will, an 18-speed bicycle where the front and rear sprockets have been replaced by a pair of fattish cones. Instead of the stepped 18-speeds, you suddenly have gears like fifteen-and-a-half, or twelve-and-three-quarters.

Inside a CVT transmission, that’s essentially what’s happening. Instead of cones, you get a pair of v-sectioned pulleys that can each squeeze or expand to change their diameter. Because the belt must always stay the same length, as one shrinks, the other grows, in an infinite number of variations between top gear and lowest gear.

In the little DAF, that drive was an actual rubber belt, and it wasn’t exactly the most reliable thing in the world. They would break, and there are stories of ladies having to temporarily use their stockings to attempt a quick fix.

Subaru’s second crack at CVTs was with the “Lineartronic” transmission, introduced in 2010 with the Legacy and Outback

That wasn’t the only weird thing about the daffy DAF. Because reverse involved simply running the transmission backward, it had the same top-speed in both directions. At the now-defunct annual Dutch backward driving world championships (yes, really), the DAF proved itself unbeatable. There was also a control on the dash that would allow increased vacuum to cause the CVT to old lower gears and enhance engine braking – you could literally turn up how much it sucked.

Because each of the DAF’s rear wheels was propelled by its own drivebelt CVT, you had a sort of weird limited-slip arrangement. Handling in icy conditions was euphemistically described as “interesting,” even though power from the 590cc flat-twin engine was very modest.

Later, DAF would be snapped up by Volvo, which would eventually coincide with the CVT’s appearance in a motorsport that dovetails nicely with our so-equipped WRX: rallycross.

For some reason, Volvo decided their DAF-engineered 343 (a rear-drive hatchback we never got here) needed a bit more rough-and-tumble to its image. They therefore entered it in the European rallycross championships in the late 1970s, equipped with a 1.6L turbocharged engine and a DAF-designed CVT. Surprisingly, it did pretty well.

That wasn’t the only foray for the CVT into motorsport. Having a continuously variable gearset at the ready means that it’s possible to hold the powertrain right at its peak output level, a concept which attracted interest at the highest level. The Williams Formula One team experimented with a CVT transmission in the early 1990s, and while there were teething troubles with heat management, the potential was there. Sensing that only the best funded teams would be able to solve the associated transmission cooling issues, the FIA immediately banned the CVT as a forbidden performance enhancer. They also put the kaibosh on Audi’s early attempts to use a CVT in WRC-level rally racing.

For most Canadians, our earliest experiences with a CVT transmission came aboard a snowmobile. Makes perfect sense, then, that the first CVT-equipped car to reach Canadian shores in any numbers was the humble little Subaru Justy. Emphasis on humble.

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto

TheBulletin.ca Journal of Downtown Toronto